50 Stories Part 8: Day and Night, They Were the Ones

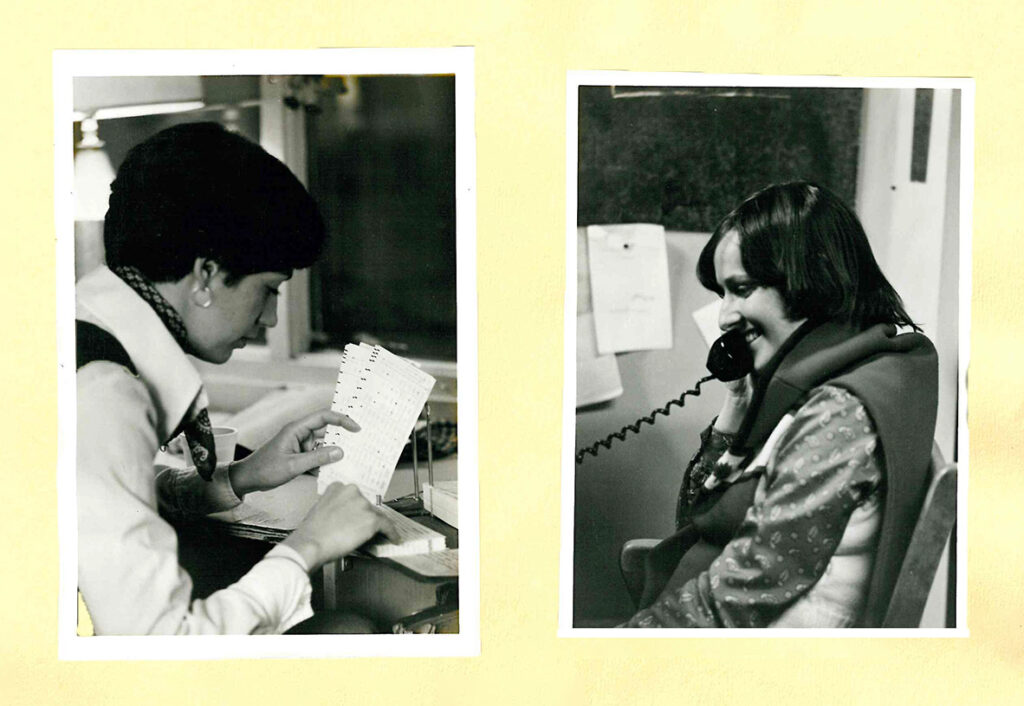

From the first days of the Drug Information Centre, volunteers have been key to its success. Since most early volunteers did not have any formal training in counselling, it was not uncommon to run into difficulties. Emil Roessingh, both a volunteer and Volunteer Coordinator recalls:

“There were times when I went out in my old Chevy sedan and people got violent in my care when I was trying to drive them to the Drug Centre. Had to hold them down in the back seat until we got there. I went in to talk to the Director, maybe 10 or more years ago, and she was pretty amazed to hear what we had been doing in those early years. We could have gotten into all kinds of trouble around liability and car insurance, but we never did. It was quite amazing. We never had a fatality, we never had anyone overdose, although we came close a few times. We dodged all the bullets.”

[edgtf_blockquote text=””We never had a fatality, we never had anyone overdose, although we came close a few times. We dodged all the bullets.” – Emil Roessingh” title_tag=”h2″ width=””]

The original volunteers were interviewed and screened, usually by Emil and Ken Low. They ranged in age from 14 to 60, and there was no shortage of willing people.

Volunteer Alan Garrett remembers: “We were basically picked because we were seemingly normal and appeared to have some knowledge of drugs and an inkling of what to do when someone was having a problem with them.”

No training manual existed in the early days but topics discussed included drugs and their effects, counselling, policy and procedure. Emil recalls:

“They would do lifeboat kind of exercises, rate yourself on your characteristics like introverted or extroverted, non verbal exercises. We were kind of reluctant to take on volunteers who, let’s say their brother or daughter had committed suicide on drugs. We looked for people who seemed quite stable, and hadn’t suffered any major trauma in the last year or two and could handle a crisis on the phones.”

Dee Clark, who volunteered via the Junior League, remembers:

“There was a young man, about 18, who was much more aware of what was going on with his peers that did some of my training. We had to have a good knowledge of how to deal with callers. During the orientation, once you were designated a position, there was a mentor monitoring your progress, identifying what the problems were and how you dealt with them.”

Early volunteers also attended events and at hospitals. Ken recalls:

“Michelle Calvert was very capable, very effective, the perfect volunteer. On one occasion, we were called to the Foothills hospital where a girl had been picked up by the police and dropped off at Emergency. She was out of control, hostile, aggressive and fearful. They had her locked up in a room with a couple of people guarding the door. The hospital staff were frightened and didn’t know what to do and they had been told often enough not to go in. As we walked into the room Michelle just started humming, and we very quietly started walking towards her. We reached out and gave her a big hug, and then sat down next to her rocking and humming. She calmed right down. It was a great demonstration, because staff were watching from the other side of the door, and it didn’t not cross their minds that this was a better technique.”

Alan Garrett describes the crisis intervention role:

“As I remember, we had an average of 100 calls a day of all types, everything from heroin addiction to suicides and domestics. Barbiturates, speed, over-the-counter drugs or anything that could get you ‘high’ and screwed up. I recall breaking in a new volunteer one night. At about 1:30 am two police officers 1-2-3 tossed a guy right through the front door. He was trussed up in a straight jacket, frothing at the mouth, and screaming bloody murder. This was normal to me. The volunteer in training took off out the back door and was never seen again. I remember losing a couple of teeth, having my ribs bruised twice and receiving numerous cuts and abrasions. To the uninitiated, working at night could be absolutely frightening.”

By the late 70s, volunteers had to be at least 18 years old, complete 3 weeks of formal training, and commit to one shift a week with ongoing training. They were there to get the caller to a safe level, assess them, refer as needed, and leave an opening for call back. 70 volunteers were supported by resource professionals. Practicum students from Mount Royal College and the University of Calgary provided additional support. Many people working in related social service agencies were volunteers, facilitating coordination amongst agencies.

The front door was locked at 9 pm, and a number of other security measures were in place. A tracing agreement existed with Alberta Government Telephones if medical or psych help was needed and the client would not volunteer their location. However, calling this 611 number could take up to 4 hours, and the caller had to be kept on the line.

Judith Ryan recalls eight-hour phone shifts in 1976, usually with two to four other people:

“It’s a really happy memory for me. There was very good team spirit there. We all supported each other. There was no competitive stuff going on. We consulted each other a lot, all the while doing education for the new volunteers. Friendships developed for sure. I feel grateful. Sometimes you think, oh that was nothing, but when you dig it all up, you realize it was meaningful.”

[edgtf_blockquote text=””I feel grateful. Sometimes you think, oh that was nothing, but when you dig it all up, you realize it was meaningful.” – Judith Ryan” title_tag=”h2″ width=””]

By the end of the 70s, it was generally recognized that there were two advantages to using volunteers for crisis calls. First, they became involved as part of the community in the solution of a wide variety of problems. Equally important, it meant a large number of people became prepared to deal with crisis situations not just at the Centre, but in their own work place, in their homes, and in the community.

The 1975 volunteer manual noted:

[edgtf_blockquote text=””Often it is thought that volunteers are used only because it is less costly than paying professional staff. This is simply not true. Professionals alone can never solve mental health needs. It is only when citizens of the community commit their time and energy to helping each other we have any hope of creating an atmosphere in which people know it is acceptable to ask for help and are likely to receive it.”” title_tag=”h2″ width=””]

In a variety of reports, other social agencies described the Centre’s volunteer program as the most successful in Calgary in terms of getting young people engaged. Volunteers felt an involvement in, and therefore a commitment to, the overall operation and direction of the Centre; a goal for volunteers that continues to be central to Distress Centre today.